Two Ladies, George Elgar Hicks, c. 1890 http://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/yourpaintings/paintings/two-ladies-17670

NEW YORK’S MYSTERIES.

“Van Gryse ” reveals the Devices of two Female Would-Be Swells.

Any one who has been a student of life in the metropolis, who knows the faces on the avenue and in the lobby on first-nights as well as he knows those on the Rialto and Wall Street, can not but have noticed that new feminine type which has come to the fore in the last twenty years, but which is as yet unclassified.

No one seems to know under what head this type should come, or what name to call it. Yet every one knows of it, and a few people have watched its gradual development with thoughtful interest. It has two or three salient characteristics, but none of these are as yet prominent enough to warrant one in classifying it as a new specimen evolved by metropolitan life.

The women of this class seem to be female prototypes of the cheap swells among men. At certain places during certain hours of the day you may see them — not in large quantities, for they are not a numerous order, but scattered through the crowd of well-dressed fashionables. The casual way-farer, though he may have been born and bred between four brick walls and have never seen the sunset except at the end of a street through a cobweb of telegraph wires, may pass them by unthinkingly as women of the patrician rich world. For they are perfect in every outward appointment of elegance and good taste.

An accomplished and sharp-eyed flaneur will notice that their smooth completeness of appearance is here and there ruffled— there is too strong a suggestion of rice-powder about their faces, their shoes are worn a little, and though they assume a look of bland and somewhat haughty complacence, their glance is at times restless and quick. They appear to be nervously on the alert to apprehend every admiring and approving look directed toward them. They expect and desire admiration, and though they make a good attempt to hide this expectation, it sometimes will not be hidden.

There are generally two of them — a mother and a daughter — and a stranger passing them would say to himself: ” There go two typical, well-dressed, aristocratic New York women of the highest class.” It is a natural supposition. They look as if bom to every luxury and comfort. In dress they are perfect — not merely perfect in the general air of their clothes, but perfect in detail. They look healthy and fresh and blooming. Their hair shines as though a maid brushed it by the hour every day. Their lips are red and smooth, and their eyes clear. They wear the newest fashion in everything — not such new fashions as will grow cheap and shoddy, but the new fashions which will only be adopted by the rich and exclusive. When a fashion falls to Fourteenth Street, they are done with it forever.

In air and appearance they look as if they were somebody.

They do not appear to notice the passers-by, but they forge along with a self-confident, haughty swing, their eyelids indolently drooping and their mouths curved into smiles of rather blase indifference. The daughter — you may see her almost any week-day morning, shopping on Twenty-Third Street — is rather pretty and very good form. She is a slender girl, about twenty-five, dressed always with quiet elegance. Her face, which is delicate, almost sallow, with dark eyes and a few locks of hair on her temples, is marred by a somewhat arrogant and cross expression. She looks like a young lady who was spoiled and could be querulous if she were thwarted.

She appears to lead the life of a woman of means and fashion. In the morning, in her warm street-suit and rich furs, she goes shopping. Sometimes her mother is with her–a pleasant-faced and refined-looking woman — but generally she is alone. She always shops in the best and most expensive stores, and she has a way of asking for what she wants which makes you think she could buy up the whole place if she wanted. On the contrary, however, she is almost invariably dissatisfied with the wares placed before her. She seems to disdain them, and an air of scornful irritation crosses her face as she pushes them aside and goes away. When she does make a purchase, were it but a spool of thread or a handkerchief, she would not dream of carrying it. It must be sent. And, as she gives the address, she leans across the counter and speaks it very low.

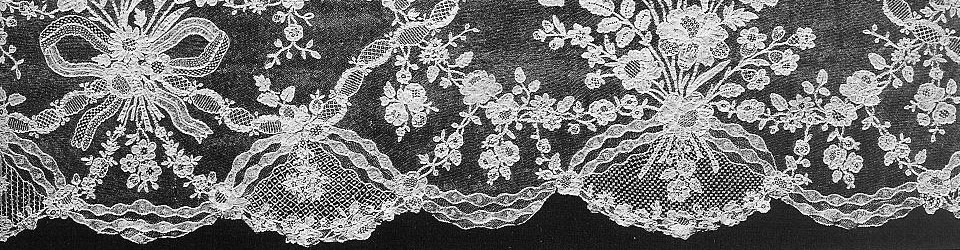

At all the openings of the most expensive places for hats and women’s clothes she is present. With her lorgnon up, she goes peering about at the new chiffons. She takes many of them in her hand and examines them disparagingly. They rarely suit her. When she was in Paris, last year, she saw just those same things — and now they are old and passe. The only way to get your clothes and have them at all chic is to go over there yourself and buy them. A modiste’s taste is invariably inclined to be shoddy.

When she gets out into the crisp winter sunshine, she tucks her trim little hands into her sable muff and walks briskly up the avenue, “toward home.” All the fellows in the club windows make flattering comments upon her as she swings along — a most attractive figure, with her neatly hung skirts, her pointed shoes, her close hat setting so snugly over her beautiful, smooth-braided hair, her sallow, high-bred face, with the rice-powder thick on the bridge of her nose, and her general air of calm unconcern. When she gets far uptown, she turns suddenly to the left, and, walking down a block, waits on the corner for a car. While she stands here, one sees how nervously alert and sharp this young woman’s indifferent eyes can become. They shoot anxious glances up and down the street. When the car comes, she springs into it with undignified speed, and nestled in a corner of it, her feet buried in the straw, the draughts blowing her hair about, she is borne across town to regions of corner-groceries and dingy boarding–houses, unkempt children, and frowsy maids-of-all-work.

She does not stay in this obscurity for long. That evening, at half-past eight, she and her mother have just rustled into their seats in the parquet for a Bernhardt first-night. She has on a pale-gray dress and wears some long-stemmed Jack roses fastened on her corsage. Her pale-gray wrap is thrown back to show these, for Jack roses are very rare at this season.

Her black hair is braided up under a little gray-gauze theatre-hat. She is altogether as well dressed as any one in the house, and many people look at her and ask who she is. Nobody knows, however. This is particularly strange, for she appears to know every one who is any one. She points them out to her mother, speaking of them with intimate personal comment, as though they were her friends since childhood :

The lady to the right, in the red hat, is Mrs. So-and-So. She has grown fat since she was at Lennox — the So-and-So women were always inclined to run to fat. That was Tommy Thingumbob there by the door. Isn’t he getting bald ? He must be tired, poor fellow ; he was up till all hours last night leading Mrs. Montgomery-Jenkins’s german. That girl there, with the turned-up nose, is the youngest of the Marshmallow girls — Toosie. They say she is going to marry young Doosenbury — the Doosenbury whose sister eloped with the coachman. Awfully sad affair. It nearly killed her mother. Betty Smith is sitting in the first row of the balcony with the Tompkinses. Betty looks very pretty to-night, yellow becomes her — and so on, and so on all through the evening. To hear her talk, you would think this young woman the most intimate friend of these people, upon whom she comments in rather a loud key. Then, when the lady next her is looking at her with curious admiration, she suddenly feels that the little filagree-edged comb is slipping out of her back hair, and draws off her glove that her hand may be free to readjust it. The hand thus revealed is wonderfully slim, white, and delicate, and is covered with pretty rings — not magnificent rings, they are not the thing for a young lady, but dainty, pretty rings of small, glittering stones.

Half-an-hour after the performance is over, she and her mother are in the corner of the cross-town car, on the last stage of their homeward journey. They sit close together, for it is biting cold. The people in the car are a sordid-looking lot, who stare stolidly at the two ladies. Through the rattling windows come in freezing blasts of air, and no matter how deeply you bury your feet in the straw, it is impossible to keep them warm. When they finally get to the wretched boarding-house where they live, it is past twelve and the house is dark. They stumble upstairs, tired and stiff, to the two tiny rooms, under the leads, which is their home. It is so cold up here that there is already a skim of ice on the water in the pitchers, and before they retire they spread their heavy ulsters and cloaks over the beds to act as coverlets. The mother is soon asleep, but the daughter, the ruling passion strong even in an atmosphere like that of a cold-storage warehouse, dallies long and lovingly over the putting away of her finery, smoothes it out, hangs it up, puts it into boxes, and folds it into bureau-drawers, finally becomes so engrossed that she takes out some of her new costumes still in process of construction, and, shivering in her meagre deshabille, holds them off at arm’s length, rapturously gloating on their beauty.

The creating and wearing of a new dress is the great event of her life. All morning she and her mother sit up in their little room, their feet against an oil-stove, cutting, snipping, and fitting on. The solemnity of the occasion is such that they do very little talking, but bend over their work in absorbed silence. An observer would hardly recognize them as the two aristocratic ladies who created quite a sensation at “Fedora” last night. The mother is now a fat and somewhat blowsy person, shrouded in a voluminous “Mother Hubbard,” her front hair twined round hair-pins. The nymph-like daughter looks thin and haggard in the searching light; her curls have gone, and her hair is wound up in a tight little knob on the back of her head. Her wrapper is dirty and faded, and hangs round her long, straight figure in limp folds. Even her rings have disappeared, locked up in a little box on the toilet-table.

In the afternoon she will go for a stroll on the avenue, and come home at half-past four, happy in the consciousness that for two hours she has been a swell. Such is the life of this modern Cinderella. She cares for nothing but this daily masquerade. Her existence is singularly lonely and profitless. She has no “circle,” no friends. She will not associate with the people in the boarding-house — the feeble, half-starved, shabby-genteel kind which haunt such barren places — and she has no means of knowing any other sort of people. The goal of her ambition is to be a fine lady, not in fact, but in appearance, and for this she lives.

She and her mother have a tiny income, left them by her dead father. They are both remarkably clever dress-makers, and if they had chosen to ply this trade, they could have placed themselves in thoroughly comfortable circumstances. But the daughter would not hear of such a thing. Their talents are employed to copy the various dresses she sees in the shops, on the streets, at the theatres, in order that she and her mother may make a good showing when they walk abroad.

Their manner of living is poor past belief. They are only half-fed, and certainly half-frozen. For sometimes the materials that the daughter chooses to buy are extremely expensive, and when there is a particularly fashionable first-night, they save out of their breakfasts and dinners enough to buy the two best seats in the house.

They always buy these themselves. The young lady has no followers, no beaux, no best man. The men whom she sees at the boarding-house are not of a kind to suit her elegant taste, and the men whom she sees on Fifth Avenue are unattainable. For, with all her faults and frivolities, she is a cut above vulgar sidewalk flirtation. She wants always to do the correct thing, and she would as soon think of bowing to a man she did not know as she would of wearing a bustle. Moreover, she is not particularly fond of men or flirtation. If they look at her admiringly on the avenue, she is quite satisfied. She would rather a great deal have one of those long, new cloaks, edged with Russian sable, than a lover. Such capacity for feeling or emotion as she possesses has all been swallowed up in her inordinate love of dress. She is one of the products of the life of a metropolis — the husk of a woman, a creature entirely passionless, heartless, and soulless.

New York, January 7, 1891. Van Gryse.

The Argonaut [San Francisco, CA] 14 August 1893

Mrs Daffodil’s Aide-memoire: Well, really…. Mrs Daffodil feels that the author is being unduly severe upon the young woman who would rather have a cloak edged with Russian sable than a lover. The cloak is assuredly a better value. The mother and daughter lead a sad enough life without being excoriated for their little deception. One suspects that class distinctions and the vulgar subject of money enter into this prejudice. It is doubtful that the author would have called Mrs Vanderbilt or Mrs Marshal Field of Chicago, “heartless” or a “husk of a woman” for her “inordinate love of dress.”

Mrs Daffodil invites you to join her on the curiously named “Face-book,” where you will find a feast of fashion hints, fads and fancies, and historical anecdotes

You may read about a sentimental succubus, a vengeful seamstress’s ghost, Victorian mourning gone horribly wrong, and, of course, Mrs Daffodil’s efficient tidying up after a distasteful decapitation in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales.