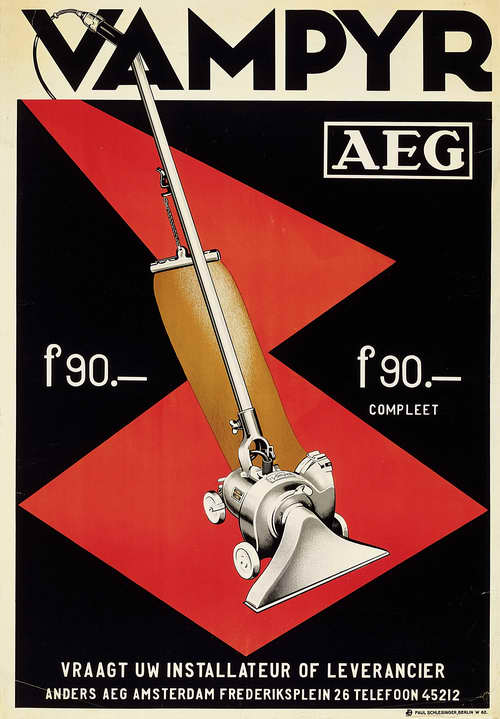

The Vampyr Vacuum. Source: http://vacuumland.org/

SUCTION

“My vacuum cleaner wants me dead,” confided Mrs. Grenfell from three doors down, when she came over to borrow a cake tin Wednesday morning.

“Dear me,” I murmured. “What brand is it?”

I really couldn’t think of anything else to say. I knew that Mrs. Donald Grenfell, while a friendly neighbour, had a reputation as an accident-prone and slipshod housekeeper. “A few socks short of a full load,” was how my friend Glynis unkindly put it.

Her kitchen lino was of an uncertain smeared hue and in the corners you might see small drifts of crumbs. Any food she offered was apt to have unappetizing additions like the long black hair Glynis had once pulled from the centre of one of Mrs. Grenfell’s unfortunate baked custards.

She was the sort of woman who was always hobbling on a sprained ankle from tripping over soft toys on the stairs. Her hands were mottled with plasters from knife cuts and she once had to be rushed to hospital with an allergic reaction to furniture polish. Her children were widely known to be spillers.

Her husband Donald was generally agreed to be a bit of a mama’s boy, but an otherwise perfectly adequate husband. He took their three children out to parks and sports so she could have time to herself and observed anniversaries and birthdays with sensible, if not romantic presents. But, entirely by accident (sound carries over the back gardens), I had heard a row at the Grenfell domicile in which the words “pigsty” “little savages” and “basic standards of decency” figured prominently.

So when Mrs. Grenfell told me that her vacuum cleaner was out to get her, I understood it to be a metaphor for her dislike of housework, or, more charitably, an expression of her despair in the face of chaos.

At my invitation she sank heavily into a kitchen chair.

“It’s a Whiffo 2000. The top of the line model with all the attachments,” she said with a kind of muted horror. ”It was a gift to my husband from his mother.”

She sighed, pushing a frizzy lock of hair back from her forehead. I poured her a cup of tea.

“His mother is one of those superhuman housewives—spices in alphabetical order, laundry hung in categories: towels at this end, underwear at that. She’s got the same model. I know he never has any trouble with it. I swear he loves the blessed thing—always going on about the 4 hp motor, its large capacity bag, and the turbo-suck feature. I think you could invade a small island nation with the damned thing,” she finished bitterly. Then she burst into tears.

I made soothing noises and presently she sat up again and tugged at the ankle elastic of her sweatpants.

“See this?” she demanded as I recoiled. “This is just the latest!”

There was an ugly red welt on her ankle, deep enough to suggest a bullwhip or a piece of flex.

“There’s a match to that on the other ankle,” she said. “The vacuum has a retractable cord. Every time I try to retract it, it balks and then whips around my leg. Donald says I just don’t know how to do it properly.”

She took a desperate swig of tea.

“It has a long snout that you plug the attachments into, but it keeps trying to wind around my neck when I’m not looking,” she said, taking off her sweatshirt and showing me strange ribbed marks on her back and throat. By her description I gather it was rather like that statue of Laocoön and his two sons entangled in giant snakes. I began to wonder if the mild Mr. Grenfell had specialized tastes in the bedroom and this was her cry for help. I also wondered how I could tactfully offer her the number for the Battered Women’s Shelter.

She put her sweatshirt back on and shoved her pants elastic back down over her wounded ankles.

“I don’t suppose there’s anything to be done about it,” she said dully. “He says I’m to blame for not making friends with it—that’s the way he talks—and that if he were in charge, the house would be immaculate, just like his mother’s. I know he gets fed up, but he just doesn’t understand. The vacuum hates me. It’s like a vicious dog that will only obey one master. “And,” she lowered her voice, “I know it talks to the other appliances. It’s only a matter of time before they all start in on me too. The children love smoothies, but I’m afraid of the blender. It just flashes those shining little knives and growls at me. The toaster wouldn’t let go of the toast one day and as I prized at it, it seized my finger. Second degree burns,” she finished, biting her lip. “He told me that I was just careless.”

She looked up at me. “I know you don’t believe me,” she said. “I can’t believe it myself. Everything thinks I’m so clumsy, such a terrible wife and mother. But I can clean and clean and while we’re in bed, the vacuum gets out of the broom cupboard somehow and blows dust all over everything. Once,” she leaned over and gripped my wrist painfully “they even put bleach into the toilet, knowing that I would be cleaning it with ammonia. I got the vent fan on just in time. Nothing I touch ever goes right on account of the damned machines!”

I was genuinely alarmed. Somebody had a death wish for her in that house, but I didn’t think it was the vacuum cleaner. Could dingy laundry and unwashed floors truly drive a man to murder? I was still pondering this when she stood, clutching the cake tin like a shield. “I’ve got to do something,” she said, pale and resolute. “Make a stand before it goes too far. The vacuum’s the ringleader. The dust stops here!”

She stumped down the back steps. I thought I heard her say, “Ball pein hammer” as she went.

The next day I was awakened by a frantic banging on the door. It was Donald Grenfell, both dusty and incoherent. I threw on a robe, called 999 and rushed with him to their foyer. His first thought on finding her missing was that she had gone out to buy bloaters for his breakfast. He was fond of bloaters. When the children began clambering for their breakfasts, knocking over a full carton of cranberry juice in the process, he went to find a mop.

It was then that her husband had found her in the broom cupboard. She was hunched up in a heap, covered in a fine grey dust. He mistook her for the upright vacuum bag and was beginning to close the door when he heard a soft moan coming from the dust-ball-covered mass. Brian, my paramedic friend, said that the police were looking into the matter of whip marks all over her body, hinting darkly of suburban orgies and nameless sexual tortures.

She was in hospital quite a long time. Just to be neighbourly, I took over a shepherd’s pie and while I was there, I offered to tidy the kitchen. Donald willingly accepted. He was half out of his wits trying to mop up after the children and placate his mother who had come at his frantic call and had stayed to gloat. I got everybody but the mother out of the house with tickets to the cinema. Donald told me in a hushed voice that Mama was in his bedroom and was Not to Be Disturbed.

“You will remember?” he said anxiously. “My mother isn’t strong and needs her sleep after travelling all the way down here.”

The way he talked, his mother was some frail, reedy pensioner who lived on broth and pale sherry. I knew better. One couldn’t miss the coloured photo of her over the fire in the lounge: she looked like a sergeant-major in a perm.

I shooed him out.

“You’ll miss the Coming Attractions,” I chirped. As he made for the front door, I heard his mother’s voice ring out from the stairs. I busied myself quietly at the sink.

Mrs. Cynthia Grenfell had been a home economics teacher and had an authoritative, carrying voice. She was holding out a tempting vision to her son: the lure of a quiet, clean, well-regulated home. Send the children off to boarding school and move in with me, she was urging. She cited the obvious arguments of health and hygiene and suggested that a wife who was such a careless housekeeper must surely be deficient in matters of intelligence, fidelity, and personal morality. “Not your equal” and “beneath you” were two phrases that I caught as I wiped the dishes dry. “Besides, how can she love you and not see that this—this—chaos is destroying your health and happiness!” she demanded dramatically, sniffing into a tissue. The dust in the house was playing hob with her allergies, but she contrived to make the sniff express a mother’s sorrowful love.

“If she really cared about you….. You can be packed and ready to leave at a moment’s notice. Just go upstairs and put a few things in a bag. Remember how we used to play Scrabble of an evening in front of the fire? Your room is all ready for you.”

At this, I was so incensed that I nearly switched on the disposal with a spoon in it.

I heard Donald go outside. The shrieking from the restive children died away down the street. There was a murmuring from the hallway outside the kitchen. I peeked around the corner. The elder Mrs. Grenfell had opened the door of the broom cupboard and was muttering. I supposed she was complaining to herself about the condition of the cupboard until I heard her laugh quietly.

“That’s right, my pet, you’ve done a superb job! Here’s a taste of her hair—you’ve vacuumed it up often enough. You’ll get as much of her blood as you like just as soon as she comes back.” She laughed again. I crept closer. The vacuum was making a humming noise like a contented cat and I swear she was stroking its bag.

“Yes, yes, you’re mother’s own darling….”

I let myself out of the back door. I needed to think. The vacuum had been a present to her son, the younger Mrs. Grenfell had said.

Mrs. Grenfell, Sr., left the next day. I heard her through my front door as she stood by the car dictating a list: the name of a solicitor who would know the right judges–judges who could be counted on to be sympathetic to a beleaguered husband and would award minimal child support and alimony to a lazy, inadequate wife. The name of a distant boarding school for the girls and a Yorkshire military academy for the boys. The date and time she expected him to arrive at her house to start his new life. A reminder to change the beneficiary on his life insurance policy to herself.

After she had left, I darted across the back garden and let myself into the kitchen. Donald was sitting at the table with a cup of tea, looking rather pole-axed.

“Ah, Susan,” he said despondently, “how kind of you to come.”

“I thought I’d do a light cleaning today,” I said coolly, “just to freshen things up.”

He nodded vaguely. “I’ve got to get to the office,” he said, standing. He hesitated, then said, as if he had just made up his mind, “The children are staying with friends until—other arrangements can be made. It seems probable that we, that is, I, shall be moving away soon.”

“I’m sorry to hear that,” I said. “In that case, I shall do a good turn-out. You’ll be wanting to list the house with an estate agent.”

“I shouldn’t be surprised,” he said, brightening. He went out with a new vigour in his step. He had never once mentioned his wife.

After he left, I went to the hall and examined the scene. There were strange circular marks on the lower half of the cupboard door. The wood was raised, like giant welts. I steeled myself to open it. The vacuum cleaner crouched beneath the coats, its chrome fixtures gleaming in the darkness. It followed me easily and I plugged it in. It seemed to me that it snorted derisively.

“Oh, no you don’t,” I said, pouring out the jar of ball bearings onto the floor.

Later, after I had apologized to Donald, I carried it away under the pretext of seeing if I could find a replacement. I made sure it was in pieces—belts cut, cords removed–before placing it on the curb on rubbish pickup day. The pickers at the tip were always on the lookout for nice items to repair and I didn’t want this particular machine coming back to haunt me.

After my abominable carelessness with their vacuum cleaner, some little coolness sprang up between the Grenfells and myself. However, it didn’t much signify: Donald followed his mother’s instructions to the letter. The children were packed off with trunks of woolen underwear, pocket handkerchiefs, and hockey sticks. I saw the notice of the divorce in the papers. The house was sold and the now ex-Mrs. Grenfell moved away just before Christmas.

She came to say goodbye before she left.

“I somehow think that the loss of the vacuum cleaner was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” she said plaintively. “Oh, I’m not blaming you, mind,” she said hastily. “I think he blamed me for breaking it the day it attacked me. He’s right. I started it. I wouldn’t be bullied any longer! But,” and she looked puzzled, “I simply don’t remember attacking it. I opened the broom cupboard, then there was a loud whooshing noise, and the next thing I knew, I woke up in hospital. The police asked me some very odd questions. It’s all very worrying.”

I bought Mr. Grenfell a new vacuum, of course. A Whiffo-3000 with the upgraded lint-o-matic sensor feature and a full collection of accessories including some of unknown uses that looked like exotic marital aids. One was rather like a fish spear with bristles, which I believe you were supposed to use to clean window blinds. I like to be thorough so I assembled the sweeper and gave it a test run. With her allergies, Mrs. Grenfell, Sr. had left behind baskets of used tissues–some spotted with her blood. The new vacuum devoured them as well as some bloodied dental floss from Mr. Grenfell’s bathroom. I had a quiet word with it as I packed it back into the box. Apparently these things are like young geese—they imprint on the first thing they taste and it is child’s play to manipulate them. In the event, I delivered the vacuum to scant thanks from the elder Mrs. G. who slammed the door in my face.

I read later in the paper of the shocking murders in the quiet village of Camden Chippenwell of Mr. Donald Grenfell, late of Deeping North and of his mother, a very well-respected lady who had been keeping house for her son. The paper did not stint on the gory details. Donald had been disembowelled and stabbed repeatedly with what police believed to be a fish spear while the elder Mrs. Grenfell was found strangled and violated. The paper, after wrestling with the public’s right to know, hinted darkly at the unnatural penetration of a number of unorthodox orifices. “Gutted with her insides sucked out,” commented the coroner, adding that he personally believed it was the work of a homicidal maniac and that the public should be on their guard.

The tabloids had a field day with headlines about The Whiffo Wacker and The Hoover Horror. With the unfortunate American yen for alliteration over accuracy, the Associated Press picked up the story of the Karpet Kleaning Killer.

It was fortunate that the ex-Mrs. Grenfell had an alibi—at the time of the murders, she was being filmed while Evie and Janet, the presenters of the popular television show Crazy Clean, berated her about the coliform bacteria on her cooker. Happily, a keen assistant to the owner of Whiffo Ltd. saw her on the show and immediately hired her as a product tester for the company after hearing the story of her cleaning misadventures.

“She has a real gift for detecting hidden flaws in otherwise serviceable products,” read the press release announcing her hiring. “We are proud to welcome her to the Whiffo family to enhance our never-ending commitment to our customers’ health and well-being.”

The assailant was never caught and the case passed into local folklore. I myself have switched to one of those manual rotating brush sweepers that are used to pick up crumbs in quiet hotel lobbies and family restaurants. One can never be too careful about household safety.

Copyright @ 2012 Chris Woodyard. All rights reserved.