DRESS IMPROVEMENT

Mrs. Jenness Miller Entertains a Large Audience of Trenton Ladies

Association Hall was again crowded yesterday afternoon with an assemblage of ladies who had gathered to hear and who listened delightedly to the apostle of culture in dress. Mrs. Miller appeared in a princess gown of old rose brocade satin, with Watteau back and side draperies. She advocates dress improvement, not dress reform. The old reform was offensive and inartistic. She spoke of the relation of women and their dress, of the Syrian women and their costumes, of the peasant women and how their lives are in harmony with their apparel.

Women ask, can these changes be made? Yes, and with less trouble than the ordinary changes of fashion, and Mrs. Miller cited the wonderful changes in dress made in the past thirty years. In the age of the hoop skirt women appeared as animated pyramids. Next was the pancake age, then the kangaroo with hump on back and hands in that fashion. Then came the pancake fashion with the skirts tied back, displaying the entire form. That style was worn by saint and sinner alike and was not considered vulgar.

The next style was the Hottentottish bustle, when the greatest changes occurred. The principal reason for desiring and advocating a change of dress is to make a better race of men and women. Had the speaker the training of the coming generation of girls, she said, there would not be so many invalids. The specialists’ signs might be taken down from Maine to California. What we need is that mothers of the coming race shall have freedom of the vital organs according to the laws of nature. To accomplish this, moral courage is necessary, but in that respect most women are deficient. We are too prone to follow a leader and care too much for public opinion. Mrs. Miller then illustrated the fashionable pose and caused much laughter.

Nature provides curved lines while fashion, on the contrary, converts them into angles. Art must be true to itself and not to fashion. Art has no novelties, the human figure never changes, it is always in proportion. The women who contemplate this change need not expect to appear better at first; there will be a transition period in which they must exercise and learn to pose correctly.

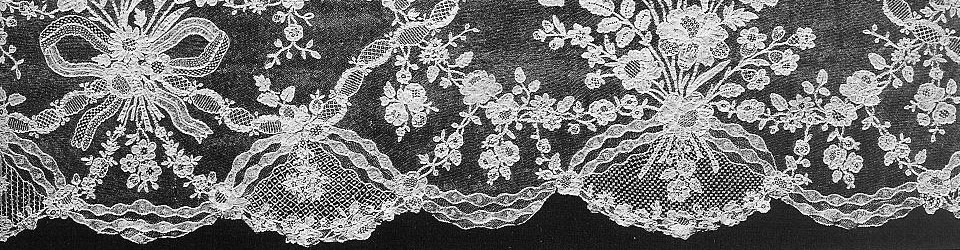

Then Mrs. Miller appeared in a street costume of tan silk, trimmed with heliotrope velvet and lace. The skirt had box plaits inserted in the seams and presented a very graceful appearance. The waist was fastened on the shoulder and under the arm. Being asked how she fastened the dress, she showed a new device which is quite novel. On the shoulder seam, around the armhole and on the underarm seam, was sewed a cord, into which the hooks could be easily fastened, without the inconvenience of looking for the eyes.

While in this costume, Mrs. Miller explained her manner of dressing and the undergarments she wore, viz., a union suit, a divided skirt of pongee silk, supported by low neck waist of the same material, and occasionally an equipoise waist without bones.

The next dress she wore was her girl’s dress, of which she is particularly fond. It was made of pale pink China silk, with Grecian border on skirt. There was a plain fitting foundation with several rows of shirring around the waist, the upper part being full and loose allowing much freedom for the raising of the chest and the expansion of the ribs. This dress is suitable for a miss or a woman of thirty years. Mrs. Miller then illustrated the ungraceful position in which many women site, having the waist line totally obscured caused by sitting on the spine. Then the rolling movement of the body was given, which, if properly exercised, places the vital organs in their proper relations, and with a regular diet will greatly improve the health.

Development of the throat and neck is desired by most ladies, but all are not aware that by tight lacing the floating ribs are compressed and necessarily push the neck bones into prominence. The two beautiful curves of nature of sacrificed for the waist line.

The fashionable woman of the period is a series of bulges that were not seen in the Venus of Milo. Upon asked her weight, she replied: “One hundred and fifty pounds in sheets and Turkish baths.”

Conventional summer dress was Mrs. Miller’s next theme. The material was an olive green lace-striped silk, with dark green velvet, lace, and gilt braid for trimmings. The dress was draped to form an overskirt which Mrs. Miller said breaks the long graceful lines and renders it unbecoming.

The rainy day costume consisted of a navy blue waterproof serge. The skirt reached halfway between the knee and the ankle; the waist consisted of an ordinary Eton jacket and silk vest. Leggings completed this outfit. In winter equestrian trousers, which furnish protection from cold and rain, are worn. Here Mrs. Miller related an amusing incident which indicated the difficulties a woman experiences in stormy weather:

A poor working woman with a bundle, baby and an umbrella in crossing a gutter was obliged to hold up her dress and in this attempt turned the little one upside down, which at first amused the speaker, but which afterward she regarded as a very pitiful sight, which showed the absolute necessity for a reform in rainy day costumes.

Many women consider the short skirt vulgar, and raise their skirts in crossing the street and display an array of underwear which is quite immodest. “I believe in legs,” said the speaker, “I am sorry for the people who have limbs.” The Almighty gave us legs as well as the men and they are not ashamed of them. Why are there so many moral cowards? We must have the courage of our convictions. When asked if the skirt could not be worn a little longer, Mrs. Miller replied that it would not be artistic and that more foot would be visible than leg, making the foot appear much larger.

Mrs. Miller believes in plenty of pockets and thinks that man’s superiority began with them. The next costume was an evening gown. It was a combination of rose satin and brocade, trimmed with ribbon, and as she was in a great hurry to conclude her address she removed her dress before the audience and put on her maternity gown. It was a princess dress which could be unlaced and enlarged by means of a cord inserted in one of the darts and another one across the front below the waist line. A Grecian drapery was fastened over it and made a very appropriate gown. Trenton [NJ] Evening Times 5 May 1894: p. 5

Mrs Daffodil’s Aide-memoire: As may be obvious from this article, Annie Jenness-Miller [1859-1935] was a dress-reformer and popular lecturer. Her “improved” gowns were often made of exquisitely rich materials by European couture houses to her designs. Illustrations of her improved fashions are less the greenery-yallery favoured by aesthetes and ridiculed by Punch, and more conventionally fashionable garments, which appear a bit blousy around the waist without a corset. She lectured around the world, except in Britain, where no agent would book her lectures and where the British public, ever conservative, refused to adopt her divided skirts. She was a prolific writer and published her own magazine, first titled Dress, but later called The Jenness-Miller Magazine. One might suggest that she enjoyed the limelight and controversy arising from her choice of crusade. Certainly Mrs Jenness-Miller had her critics:

MORAL EFFECT OF DIVIDED SKIRTS.

A WOMAN’S CRITICISM OF MRS. JENNESS-MILLER AND HER THEORIES

To the Editor of the New York Times:

To be a successful reformer one must be able to demonstrate in one’s own person the perfect confirmation of one’s theories. A homely woman might as well attempt to change the order of the universe as to influence her sex on the subject of beauty.

The success with which Mrs. Jenness-Miller, the dress reformer, has met is due not to a mental capacity in the last unusual or to any very original ideas, but entirely to the fact that she is a rather handsome woman with a fine figure, and her gowns are artistically beautiful. So far as physical well-being goes, Mrs. Jenness-Miller does, indeed, make a charming illustration for her lectures. Inadvertently and unconsciously, however, she contradicts herself when she tells her audience that divided skirts, chemilettes [a union suit meant to replace corset and petticoat], spiral garters, and the like will affect the honesty, truthfulness, and general uprightness of the race. If Mrs. Jenness-Miller really believes this, how does it happen that she, who has lived, so to speak, in these moral elevators—divided skirts, chemilettes, spiral garters, and the like—for the past five or six years, regards it as perfectly honest to sell tickets at $1 each, or $5 for a course of seven lectures, advertising seven different topics, and to make the third lecture of the course simply a repetition of her first, with fifteen minutes at the utmost devoted to the advertised subject?

Mrs. Miller’s wit cannot be listened to twice without a feeling of ennui. Her hits at man’s curiosity, suspenders, and legs, the unwinding of petticoats on a windy day were amusing when first hear, but fell decidedly flat the second time. Nor was her lecture sufficiently profound for even the dullest not to grasp her meaning in one hearing. Obviously it escapes the mind of this charming woman that although she herself has reached such a high plane in the march of progress as to call legs by their proper name and wears divided skirts, the rest of the world cannot rashly venture to put so great a strain on their mental powers as to listen to these thought-burdened theories twice in so short a time.

Mrs. Jenness-Miller by no means confines herself to the reform of undergarments. Our watches are attacked! In the first lecture, according to the watch which millions of unreformed people are stupid enough still to regard as nearly veracious, the fair lecturer greeted her audience at 11:25, and at 12:35 by the same timepiece she was gone. Yet this Venus of Reform calmly and positively declared that she had talked two full hours. When some one in the audience demurred she smilingly remarked: “Women never realize how time slips by when they are looking at pretty gowns.” We must acknowledge that if chemilettes make truthful men and women the watch had best hide its face forever.

VAILLANT JULICO.

New York Times 30 March 1890

Mrs Daffodil invites you to join her on the curiously named “Face-book,” where you will find a feast of fashion hints, fads and fancies, and historical anecdotes.

Pingback: The Rational Dress Show: 1883 | Mrs Daffodil Digresses

Pingback: She Dressed to Please Her Husband: 1916 | Mrs Daffodil Digresses

Pingback: The Woman with Five Pockets: 1891 | Mrs Daffodil Digresses

Pingback: Circus Girls Wear Corsets: 1895 | Mrs Daffodil Digresses