FROM OPERA TO “BREAD LINE.”

A New York Transition— Fashion in the Limelight, Beggardom Huddling in the Shadows— An Evening Begun Where Jewels Glittered, Ended Where Derelicts Shivered.

Last Friday night was a great occasion at the opera.

It was Melba’s first appearance there after an absence of four years, and it was this season’s initial performance of “La Boheme,” with Caruso as Rodolphe. The house alone was worth going to see. I do not believe there was a vacant seat in it. The five tiers were solidly set in lines of human faces like a mosaic.

In the two upper galleries a phalanx of standing figures made a dark fringe against the illuminated walls. Every box was full; two or three women in light-colored dresses in the front, and the black forms of men grouped behind them. The clothes these women wore represented untold thousands; the jewels must have run up into the millions.

Between the acts the corridors were full of promenading people, who kept stopping and assuring each other that it was a great performance and a great house. A stream of spectators poured in and out through the doorways into each gallery to stand on the open spaces at the sides and through opera-glasses study the boxes. They were worth a careful survey.

Some of the most beautiful women and distinguished men in New York, the Empire City of the country, were there on view. It was a great showing of the city’s richest and fairest in their bravest clothes, attired for inspection and conquest.

When Prince Henry of Prussia was taken to the opera on the gala night arranged for his especial benefit, one of his comments had been that he had never before seen “so many crowned heads together at one time.”

This, as far as I know, is the one and only occasion on which that diplomatic prince permitted himself a sarcasm. There were fewer crowned heads the other night, because, I believe, tiaras are not so much the fashion as they were when the prince was here. There were only four or five in the grand tier. One regal one, encrusted with diamonds and about the size of a tea-cup, graced the head of Mrs. George Gould, who was, to my thinking, almost the most beautiful woman in that glittering horseshoe of fashion and wealth. She is tall and slender, has black hair, large, dark eyes, and is a radiant, gracious-looking person.

There were Vanderbilt and Astor ladies who also sparkled, and some of whom were pretty women, too. I noticed that those who did not wear diamond crowns wore wreaths of leaves in their hair. A good half of the women present wore these wreaths, of a narrow green leaf, and so arranged that they had a pointed effect in the front, such as one notices in the laurel crown Virgil wears in Dore’s pictures of “The Inferno.” Black-haired women wore gold leaves, and some of the blondes wore small pink roses in round wreaths that set well down on their heads.

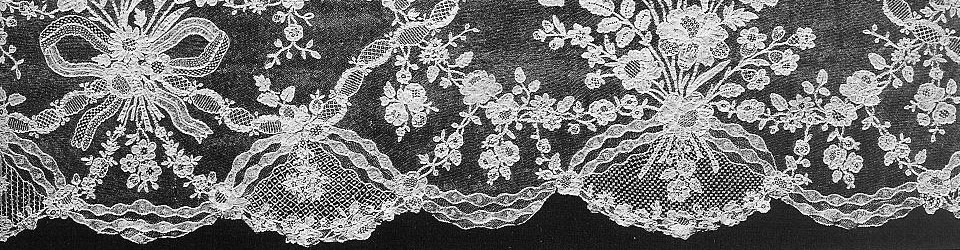

As for the jewels, they were of all kinds, long and short strings of pearls being the most popular. A good many women had on those high pearl dog-collars that give the wearer the effect of being garrotted. They are an extremely ugly fashion, but I suppose they have their uses for women who have scrawny throats. Necklaces of diamonds, or diamonds set with other stones, adorned all sorts of necks, from the slender milky-white one of the young bride, to the coarse-grained, adipose-covered one of the old matron. Some women wore necklaces pinned across the front of their bodices, where they either glittered among laces or made contrasts of color with the tint of the dress. One strange-looking girl in black velvet, with a pair of extraordinarily thin shoulders emerging from the low-cut neck of her gown, wore an enormous bowknot pin of diamonds just below her belt on one side of her stomach. Altogether it was a dazzling and splendid jewel show, a sumptuous exhibit of what New York can do.

The women thus decorated wore pale-colored dresses of soft, clinging materials. It was noticeable that black or deep-colored gowns were scarce. I saw one exceedingly handsome girl in ruby velvet, which set with a severe classic simplicity over a fine figure. This dress, and the black velvet one on the lady with the diamond bowknot, were the only dark-colored ones I saw on young women. White seemed the favorite color — white in lace that fell in mist-like softness, in clinging crepe embroidered with silver, in vaporous chiffons encrusted with rich laces and weighted with spangles, in lustrous, heavy silks and bloomy velvets. When Caruso was emitting sounds so exquisite, so melodious, so tender and beautiful that the most indifferent must have given ear, these pale-clad women sat in a motionless semicircle, their forms ghost-like under the lowered lights, the black background of listening men behind them, and behind that again the red walls of the boxes gleaming clearly under the glow of half-extinguished electric bulbs.

We talked it over afterward at Mouquin’s, as we ate oysters and drank beer, and decided it certainly had been a great performance and a great house. We commented on the display of jewels, on the beauty of the women, the splendor of the clothes, and the amount of money represented in that vast concourse of the rich and fashionable of a metropolis. Finally I said that, all things considered, I thought New York could make as fine a showing for such an occasion as any city in the world.

“New York,” said my companion, “can make as fine a showing in almost any direction as any city in the world. We’ve seen a gala night at the opera. Do you want to come and see another strange and characteristic New York sight?”

I said I did. But what and where was it? It was very cold, late, almost twelve o’clock.

“Well, Cinderella having been to the ball and seen the beau monde disporting itself, can now take a Broadway car and go down to Eleventh Street and see ‘The Bread Line.’ Does she want to come?”

Cinderella thought she did, but would she have time?

Truly it was hard to leave the warmth and brightness of the restaurant and face the streets held in the grip of an iron frost. But she had never seen “The Bread Line.”

“It will strike you with full force to-night,” urged her companion, “after all that pomp and circumstance at the opera-house. It’s just the psychological moment.”

I don’t know whether there are any “Bread Lines” in the Far West. I hear there are several in New York, but the best-known is at the old Vienna Bakery on Eleventh Street, between Wanamaker’s and Grace Church. It was established years ago by Fleischman, the founder of the bakery, who provided a loaf of bread and a cup of coffee for any human creature who at midnight should come to his bakery and demand it. No questions were asked, no qualifications required.

Fleischman, the baker, knew that the mass of those who would take advantage of his generosity would be the city’s derelicts, who live on the charity of their fellows. But he must also have known that there were often decent men who wanted bread, who were ashamed to beg for it, and who could come to his bakery at midnight to get a loaf.

It has been named “The Bread Line” because of its length. Long before midnight it extends from the door behind the bakery, midway up the block, to Broadway, and round the corner toward the entrance to Grace Church. Sometimes it is longer than this, sometimes shorter. As we approached up the loneliness of the deserted, icy street we could see it, dim and motionless, like a sinister black snake, each figure a vertebrae in its sinuous length. The cold was intense, and the men stood close together. Most of them were silent: they seemed held in the deadly grip of the frost and their own misery. We were near them when midnight struck, and with a slow, shuffling movement the column began to move forward. At the upper end we could see it breaking into dark segments, some of which disappeared into the night, while others stayed about, eating their bread in the ice-bound street at midnight.

We drew away into a darkened angle where we could not be seen, and for a space watched them. Some took their loaves, hid them under their coats, and walked away rapidly with firm, quick steps. Others ate them then and there, with a hungry, fierce indifference.

We saw several who, with the bread hidden, went back to the end of the line and joined it again. From the huge pail of coffee at the door a man ladled dippers- full into tin cups, and with his loaf of bread each recipient of the dead baker’s bounty was given a cup. Several did not take them. Most did and stood about drinking the coffee and biting pieces off the loaf. Here there were a few desultory remarks interchanged. But for the most part the whole business was executed in a grim silence.

It was difficult to see what manner of men they were. One can not stare at a brother in affliction, even when he is standing at midnight in “The Bread Line.” Many of those I saw looked as if they might be of that vast class of incompetents who live upon the city’s generosity. But here and there a face struck your eye that was not the face of the drunk, the tramp, or the beggar. We both noticed a young man having the appearance of a gentleman, who was without an overcoat and had gloves on. He took his loaf, thrust it under his coat, and fled. A fresh-faced lad, stalwart and ruddy, who looked like a boy in from the country, was embarrassed and ashamed. He kept making jocular remarks to his neighbors and then giving loud, sheepish laughs — the only sound of that sort to be heard in that dismal assemblage. He carried a new shovel in his hand, and had evidently been working among the snow-shovelers. For these and their like, Fleischman, the baker, must have established “The Bread Line.”

The column was thinning as we passed down the street to Fourth Avenue. This way and that through the still, deserted thoroughfares we could see the men dispersing — dark, furtive figures slipping away to the holes and corners where the derelicts of a great city make their homes. A step behind us caused me to turn, and I saw a tall, thin man, with white hair and mustache, and a face of an extraordinary transparent pallor, coming toward us with his loaf of bread bulging beneath his coat. He had deep-set, darkly circled eyes, and in the whiteness of his face they had an uncanny look of haggard intensity. He went by us staring fixedly before him, like a sleepwalker. I commented on his appearance, to which my companion, more experienced in the seamy side of the city, observed, laconically, ” Looks like a morphine fiend; probably lives by ‘The Bread Line.'”

The chill of the night felt sharper than ever as we went for the car. Certainly New York could make a good showing in all directions. The opera-house and “The Bread Line” would have both been hard to beat.

Geraldine Bonner.

New York, December 19, 1904.

The Argonaut [San Francisco, CA] 5 January 1905

Mrs Daffodil’s Aide-memoire: Miss Bonner was an American journalist and novelist with a keen eye for detail. While there were “soup kitchens” in England and Ireland, like the work-houses they often provided a serving of humiliation with the proffered sustenance. Cold charity, indeed. One wouldn’t wish to aid any but the Deserving Poor.

Here is a most interesting article on the Bread Line.

Mrs Daffodil invites you to join her on the curiously named “Face-book,” where you will find a feast of fashion hints, fads and fancies, and historical anecdotes

You may read about a sentimental succubus, a vengeful seamstress’s ghost, Victorian mourning gone horribly wrong, and, of course, Mrs Daffodil’s efficient tidying up after a distasteful decapitation in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales.