DRESSING ON $50 TO $200 A YEAR

By Emma M. Hooper

It is becoming an almost universal practice for husbands to allow their wives, and parents to make their daughters, a fixed allowance for their clothes and personal expenses, consequently the question has arisen as to how the best results may be obtained from the expenditure of a stated sum of money. Every woman should know how to spend money to the best advantage, but this she cannot do unless she is trusted with a certain sum at regular intervals—which sum, of course, must be largely dependent upon the income of the breadwinner of her home.

For the matron or young girl with fifty, one hundred or two hundred dollars a year, or, perhaps, even less, there must be a great deal of planning if the sum is to cover the necessary outlay for the year. It is for just such women that I have prepared this article.

DRESSING ON FIFTY DOLLARS A YEAR

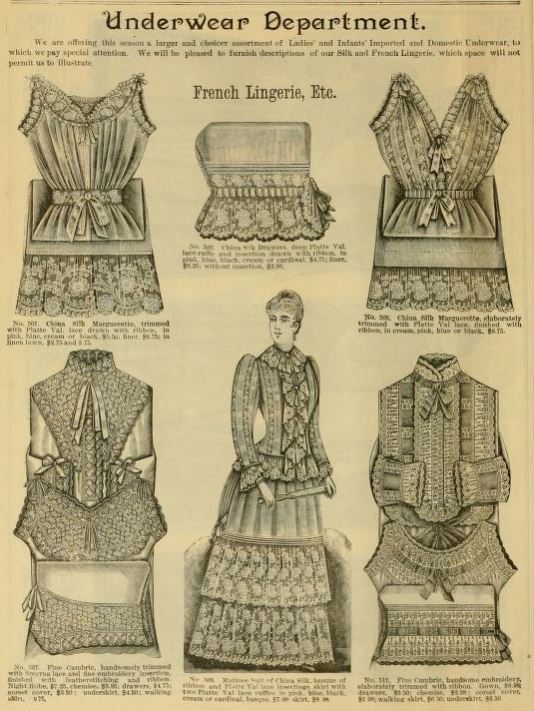

For the muslin underwear all trimming, unless it be a crocheted or knitted thread edge done at odd times, must be omitted. Unless one is very hard on her clothes, which is usually another name for carelessness, three sets of muslin underwear added each fall to the supply on hand will answer every purpose. The material for these will cost three dollars. Two sets of wool and cotton underwear for three dollars should also be added; they will, with care, last two winters. The next year buy four cotton vests at twenty-five cents, thus alternating the expense.

A Seersucker petticoat may be bought one spring for seventy-five cents, and two white muslin ones the next for a dollar and twenty-five cents, so I will count in but one dollar for the yearly average. A black alpaca petticoat for two winters will cost a dollar. It may need a new ruffle the second year. Two heavy flannel skirts may be had for a dollar and a half, and two light ones of flannelette for ninety cents. These should last three years by making them with a tuck to let out as they shrink. Only a third of this combined expense should be charged to each year, and always arrange so that these articles are not needed the same year. The woman dressing on the sum of fifty dollars must be a manager and able to do her own sewing, or she will utterly fail to make the good appearance which every woman desires to make.

ECONOMY IN SMALL BELONGINGS OF DRESS

Six pairs of hose at a dollar and a half, and two pairs of shoes at two dollars and a half must keep her shod, and this will probably mean mended shoes before the year is out. A corset at one dollar and a half may be worn a year. A pair of rubbers and parasol one year, alternating with an umbrella the second, the three costing two dollars and a half for each year. A winter jacket at eight dollars and a spring cape at three, must last three years, so I will count in the yearly average expense for wraps as four dollars, as each garment may need a little new trimming or renovating of some sort. Two pairs of gloves, cotton and kid, and a pair of mitts crocheted by the wearer will cost a dollar and a half. A new hat, and an old one retrimmed each year, will mean five dollars, and it will also mean that recurling of feathers, steaming velvet to freshen it, and the cleaning of ribbons and lace must not be numbered among the lost arts, for such accomplishments prove a great saving to the woman with small means at her command.

WHEN BUYING DRESSES, SKIRTS AND BODICES

In the line of dresses I allow two new ginghams and two cotton shirt-waists each spring, at a cost of three dollars for the materials. A Swiss or organdy, with ribbon belt and collar, every second summer, will be four dollars. A silk waist every second year will be four dollars; it will alternate with the best thin summer gown. A cheviot or serge dress in the fall will cost ten dollars with linings, etc., and will bear wearing for two years. Try and have a new fall gown one year, and a woolen one for the spring the succeeding year. A black alpaca skirt for four dollars will wear for two years. This makes a total of forty-six dollars and eighty cents, leaving a small margin for making over a gown, and for handkerchiefs, ribbons, veils, collars, etc.

These small things add much to one’s appearance, and need not be over an ordinary grade, but they should be fresh and bright. Iron out ribbon collars and veils when wrinkled, and they will last longer.

WITH LESS THAN FIFTY DOLLARS

Dressing on fifty dollars a year requires careful economy, but what about the thousands who have less than fifty dollars a year for personal use? It means well-worn and carefully mended garments, and a new wrap only once in four or five years, and a very simple hat in two. One woolen dress at ten dollars must last three years. Among inexpensive dress goods it is well to remember that serge and cheviot give the best wear. Two gingham gowns will be two dollars, and two shirt-waists seventy-five cents; a crash suit for summer, lasting two years, a dollar and a half; a couple of heavy ginghams for housework in the winter, a dollar and sixty cents; six pairs of hose, a dollar and a half, and two pairs of shoes, five dollars.

Three sets of unbleached muslin underwear will be two dollars and a half, and two sets of merino, vest and drawers, two dollars; the latter must wear for two years. A seersucker petticoat made in the fall will be heavy for winter, and washed thin for the summer, at a cost of sixty-five cents. Two flannelette skirts for sixty cents, and two red flannel ones for a dollar and forty cents will wear two years, leaving half of that amount to be charged to each year. Count five dollars a year toward a wrap once in four years, and one new hat a year. Allow three dollars a year for a pair of rubbers, leather belt, handkerchiefs and gloves, and a dollar and eighty-nine cents for renovating a gown of last year, and an average of thirty dollars is reached.

Save at least a dollar and have some magazine to brighten your lives, even if it means extra darns or patched shoes, for the brain craves food, as well as the body, clothing.

DRESSING ON A HUNDRED DOLLARS

This seems like untold wealth after the smaller income, but the girl or woman having one hundred dollars a year, and indulging a craving for amusement, will soon find it slip away unless she is very careful.

With this amount prepare the muslin underwear, sets of drawers and vests, cotton vests, petticoats, flannel and flannelette skirts, as described in the outfit for fifty dollars. To the six pairs of hose add two pairs of tan-colored to wear with russet shoes in the summer, adding shoes at two dollars, to two pairs for five dollars, allowing two dollars for hose. Corsets, a dollar and a half; rubbers, fifty cents. Parasol one year and umbrella the next will be two dollars yearly.

Every two years buy a winter jacket at eight dollars, and a light wrap for four, making a cost of six dollars per year. Two pairs of kid and two pairs of silk gloves will be two dollars and a half, and I will allow six dollars for millinery. Ten dollars is not too large a sum to allow for the many little accessories that add so much to a toilet, as collars, ribbons, belts, cravats, handkerchiefs, etc. Five dollars may be laid aside for the remodeling of last season’s gowns, and five more for the church donation and some especially-prized paper or magazine.

JUDGMENT IN BUYING DRESSES AND SKIRTS

In the spring a jacket suit of serge with a silk front and linings will be ten dollars for two years. A crash skirt at seventy-five cents, two shirt-waists within the same amount, and a wash silk waist will be a dollar and a quarter extra. One season have a white organdy gown, and the next a figured dimity, each trimmed in lace and ribbon and costing. five dollars. A less expensive cotton gown will be four dollars, and an added black skirt of taffeta at seventy-five cents a yard, eight dollars, the latter lasting two years and answering for all seasons, as will a neat silk waist at the same price. One new fall suit each year will give a change, as the second winter sees the gown of the first remodeled. Allow six dollars for this each year, as it pays to buy as nice a quality of dress goods as one can afford.

The total now shows an average of eighty-five dollars and a half, and the remainder will be needed for an evening gown for holidays, changing with an organdy. For this price one of China silk at fifty cents, with a velveteen belt and shoulder bows, and lace at the neck, will be the best purchase, and make over for the succeeding year.

As white China silk washes and dry-cleans well it is a useful purchase, lasting two seasons for the evening, and then will answer for the lining of a chiffon waist. The latter would need four yards, at sixty-nine cents, and ribbon belt and collar. By having a white silk and two or more colored ribbon and velvet belts, sashes and collars, several changes may be effected at a small expense. Very pretty sashes are now made of a full width of chiffon or mousseline wrinkled closely around the waist, knotted at the back and allowed to fall in two long ends, which have been simply hemmed and tucked on the lower edge.

WITH TWO HUNDRED DOLLARS

A person with a two-hundred-dollar income should certainly give some of it in charity. If living in the city, five dollars is a moderate sum to allow for car fare, the same for charity, and for the savings box, and another five for the church collection. An occasional concert, visit to the theatre, etc., may be counted as ten dollars, with reading matter and stationery at five. A journey for a short visit comes within the life of many, and can hardly be encompassed under ten dollars. The idea of buying the most expensive clothing in alternate years should be followed with this income, as with the smaller ones. Goods of a better quality may also be purchased with the additional sum. I can only give an average, as one person may visit a great deal, the next one seldom go out; one may be very careful in the care of her clothes, and another be distressingly careless, all of which affects the garment’s wear. With a limited wardrobe avoid striking novelties, startling colors and a large variety of shades. With the two-hundred-dollar income allow for the assistance of a dressmaker, when making the two best suits.

SELECTING THE IMPORTANT ITEMS OF DRESS

A winter coat at twelve dollars, a spring jacket at six, and a fur collar at eight, should last three years, at a cost of a little over eight dollars per year. Twelve dollars will cover the millinery, and six dollars the gloves. Count shoes as two pairs at three dollars, a pair of ties will make eight. A nice winter gown of broadcloth with velvet trimming may be counted for fifteen dollars, and may alternate with a stylish little dress of figured taffeta silk suitable for concerts, dinners, etc., each lasting two years. A black silk skirt, and an evening waist of light silk trimmed with lace, ribbon or chiffon, costing ten dollars each if both are made at home, will make the expense small when divided between two winters.

A dainty tea jacket of cashmere, lace and ribbon, costing three dollars and a half, will last several seasons. An evening gown of white net over percaline, with lace and velvet trimming, may be evolved out of fifteen dollars. Ten dollars will be used for freshening up the gowns of last year, and another ten will go for the little things—collars, cravats, veils and handkerchiefs.

For the spring buy a foulard or light wool gown one year, and a jacket suit of covert, serge or cheviot the next, the latter answering for traveling and outing wear, and the former for church and visiting. These gowns would certainly average twelve dollars each year. A piqué suit at three dollars, a white organdy lined with lawn for six, and a figured dimity for the same would be fifteen dollars. Three cotton shirt-waists for a dollar and twenty-five cents, and one of wash silk would answer for the summer.

In giving prices I take an average obtainable in New York, Chicago and Boston.

SELECTING THE MINOR ARTICLES OF DRESS

Eight pairs of hose for two dollars and a half, an alpaca petticoat with silk ruffles for two, a percaline petticoat for a dollar, and two white ones for two dollars would be a fair supply. Corsets, a dollar and a half; two heavy flannel skirts for a dollar and seventy-five cents, and two of flannelette for a dollar would last two years at an expense of half of that for each year. Four sets of underwear at a cost of six dollars may be allowed, though costing less if made at home. Three sets of mixed wool and cotton will last three years, and cost four dollars and a half. At least two pretty corset-covers for wearing with thin dresses will be a dollar and fifty cents.

Alternate parasol and umbrella at a cost of three dollars, rounding up a total of one hundred and ninety-five dollars. The small amount left is soon eaten up by a gift or two, an extra bit of adornment, such as a fluffy mousseline boa now so fashionable, a new purse, toilet articles, etc. If advice has any weight I would advise saving another five for the savings box, for it is such a comfortable feeling to know that you have even a small sum laid away for a the unexpected that is always sure to happen.

In selecting a wardrobe from season to season try to have a black gown, or at least a black skirt, always ready for use. If of silk, have it gros-grain or taffeta; if of wool, a serge, mohair, Eudora or cashmere. Do not buy in advance of the season, as the goods are then high in price, and beware of extreme novelties at the end of the season; they are too conspicuous to be forgotten.

Another thing to remember is that it costs no more to select becoming colors than others that do not bring out one’s good points. Having a gown made in a becoming style, simple or elaborate, does not increase the expense, or need not if the wearer knows how her gowns should be designed to suit her figure and complexion—the tests. When a limited wardrobe is necessary, avoid too great a variety in coloring, and under all circumstances have one gown of black goods appropriate for all seasons. By having a supply of colored ribbon collars, and one or two fancy vests and belts, this black dress will answer for the foundation of both house and street toilets, and you will always be ready for an unexpected journey, sudden visit or simple entertainment.

The Ladies’ Home Journal, Issue 1, 1898

Mrs Daffodil’s Aide-memoire: Mrs Daffodil really has nothing to add to this exhaustive analysis of dress goods and ribbons except to define “crash” for those unfamiliar with the textile as a light-weight, coarse, unevenly woven cloth of cotton, linen, jute, or hemp.

The advice to frugal ladies to accessorise gowns of a single colour to simulate variety in one’s wardrobe has been repeated ad nauseam in fashion magazines since time immemorial. Mrs Daffodil has taken this good counsel to heart: her entire wardrobe of gowns is of black materials; the restful monotony varied only by aprons of white or black, as required.

Readers will find information on how wealthy ladies spend their dress allowances here. How much fashionable gentlemen expend on their wardrobes is described here and here. An absurdly expensive bicycle costume is documented here. If one wishes to know what it would cost to be correctly presented at the Court of St James, here are all the details.

Mrs Daffodil invites you to join her on the curiously named “Face-book,” where you will find a feast of fashion hints, fads and fancies, and historical anecdotes

You may read about a sentimental succubus, a vengeful seamstress’s ghost, Victorian mourning gone horribly wrong, and, of course, Mrs Daffodil’s efficient tidying up after a distasteful decapitation in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales.

![Mrs Henry Spencer Lucy in mourning. Oil painting on canvas,Christina Cameron Campbell, Mrs Henry Spencer Lucy (d. 1919) [?1826 - 1898] by Giuseppe da Pozzo (Conegliano 1844 - Rome 1919), signed G da Pozzo Roma. A full-length portrait of the wife of Henry Spencer Lucy, who died 1890, and eldest daughter of Alexander Campbell of Monzie.In 1890 she assumed the name Cameron-Lucy in her widowhood. She is seen dressed in black with a white cap and veil, drawn back, sitting on a throne onsmall raised platform with a footstool n the carpet at her feetnext to carpeted table with a framed photgraph, small urn, ?chalice/monstrance and various other effects, holding a pice of paper in her hand.](https://mrsdaffodildigresses.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/mrs-henry-spencer-cameron-widow.jpg?w=625)